Mike Leigh (Life is Sweet, Another Year) is one of the finest and most innovative directors working today. Luckily, Americans have access to all of his films, from his early grimly funny, character-driven telefilms to his recent big-screen triumphs. His films have been unfairly slighted as being the modern equivalent of the “kitchen sink” working-class dramas of the Sixties, but he has in fact explored modern relationships from numerous angles, while also giving us numerous memorable dramatic and comic scenes as well as two of the crankiest and most oddly charismatic figures in British cinema: David Thewlis’s razor-sharp Johnny in Naked (1993) and Timothy Spall’s (Wake Wood, Comes A Bright Day) incarnation of the famed British artist J.M.W. Turner in his latest film, Mr. Turner.

Mike Leigh (Life is Sweet, Another Year) is one of the finest and most innovative directors working today. Luckily, Americans have access to all of his films, from his early grimly funny, character-driven telefilms to his recent big-screen triumphs. His films have been unfairly slighted as being the modern equivalent of the “kitchen sink” working-class dramas of the Sixties, but he has in fact explored modern relationships from numerous angles, while also giving us numerous memorable dramatic and comic scenes as well as two of the crankiest and most oddly charismatic figures in British cinema: David Thewlis’s razor-sharp Johnny in Naked (1993) and Timothy Spall’s (Wake Wood, Comes A Bright Day) incarnation of the famed British artist J.M.W. Turner in his latest film, Mr. Turner.

Leigh is perhaps most famous for an aspect of his filmmaking that is never seen by the viewer: his prolonged rehearsal period, in which he has the characters create backstories and dialogue for their characters, thus lending an incredible depth and naturalism to their performances.

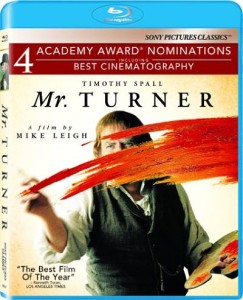

Mr. Turner will be released on DVD and Blu-ray by Sony on May 5; the package contains an audio commentary by Leigh, a making-of featurette and a deleted scene. The Blu-ray edition contains an additional exclusive featurette.

Disc Dish: Mr. Turner features incredible cinematography by Dick Pope. Could you talk about your working relationship with him?

Mike Leigh: I’ve worked with Dick Pope since Life is Sweet in 1990, and he’s shot everything I’ve done ever since. We spent years after the making of Topsy Turvy talking about this film and looking at Turner’s work. They were very generous at the Turner Bequest in London at the Tate Gallery, where you can see all of his sketchbooks; his hand-made color charts are particularly interesting. We did all that so that we could make a film that was informed by the spirit of Turner.

DD: This film is light years away from the old Hollywood biopics that tried to capture the “life of a great artist.”

Actor Timothy Spall (r.), director Mike Leigh (ctr.) and cinematographer Dick Pope on the set of Mr. Turner.

ML: I can’t imagine a biopic of Turner. Yes, I could — first of all, you’d get a fat baby, then you’d get a fat little boy who looks like Timothy Spall and who could draw, then you’d get a pimply teenager. But, I mean, this is not interesting…. The great tradition of the biopic is to make each event in our hero’s life to be significant and symbolic, of course.

I make films in which you don’t have to explain everything. Life explains itself. You walk past somebody on the street or you sit on the subway and hear a snippet of conversation for which you don’t get three chapters’ worth of explanation… You just hear something and immediately get it. You contextualize it under your own steam. That’s how I like to tell stories. It’s just real.

DD: Does your rehearsal process change when you’re making period pieces?

ML: No, it doesn’t change at all. The only difference is that you obviously read and absorb and research, and that feeds into the process. Look, here’s the thing: you can read until you’re blue in the face, you can read a million books. You can research for a thousand years. But that doesn’t make it happen in front of the camera. You’ve still got to have flesh and blood people, living and breathing and being their three-dimensional selves in front of the camera.

The work we do is character work, improvisation work, and work about how people behave, and how they talk and speak and move. All of that has to happen anyway. So all you do is absorb what you’re going to by research, and then you do all that work. The difference is, of course, that when I’m doing one of my “regular” films, so to speak, we’re completely making it up from scratch, without reference to anything. In this case we’re dramatizing real events or people.

DD: Timothy Spall has created an incredibly array of characters for your films, from the quiet, introverted characters in Secrets and Lies and All or Nothing to the cranky, stubborn Turner.

ML: He is an extremely versatile character actor, indeed. The key to it is that, although he’s very much an actor that taps into his own emotional and life experience resources, he isn’t playing himself. He’s exercising that muscle of versatility. And he’s very sensitive to the 19th century — he’s read a lot of Dickens and is very good at playing 19th-century characters. Quite a lot of the actors in Mr. Turner are. It’s just something they can get, something in their received collective memory.

DD: You’ve noted before that you don’t want your actors to bring their characters home with them. Timothy Spall does such an immaculate job one might think he did “live” as his character throughout the day.

ML: Timothy wouldn’t want to go home as Turner, not at all. What I do is about character acting is to make certain that people are not playing themselves. When an actor plays a part, she or he is in there, of course, they’re drawing on their own resources. People once thought that David Thewlis became the character of Johnny [in Naked] and that Brenda Blethyn became Cynthia [in Secrets and Lies]. But if you can imagine trying to make a film with somebody who was Cynthia, or didn’t come out of character, you’d never get the bloody film made!

This is part of the discipline of what actors should and shouldn’t do. It’s not healthy to be the character all the time. It’s very healthy to be the character all the time when you’re in character. And the paradox of this discussion is that you can see all sorts of actors in films who are not in character when they’re supposed to be in character….

DD: There is a moment in Mr. Turner where Turner has become unfashionable and sees a sketch in a vaudeville show where he is mocked. Did that scene resonate with you as an artist?

ML: No, it never occurred to me at all. That happened in the film because that’s what happened to Turner. And that vaudeville sketch that you see in the film, I wrote it myself, but it did actually happen. Queen Victoria was rude about him, she hated his stuff. And that’s what you see in the movie. Other people were rude about his stuff. The film is all about what happened to Turner, really.

DD: Watching your films, the family dramas in particular, I feel like I’m seeing “snapshots” of contemporary Britain; in Mr. Turner one gets a snapshot of the early 19th century. I know you probably don’t make that a priority, but do you reflect on “the moment” when you’re assembling the films?

ML: Well, yes. For me it’s a given. With my contemporary films I’m implicitly and un-self-consciously plugging into the zeitgeist, capturing the zeitgeist, the moment we’re in. But, of course, I’m not concerned to do that. I’m not concerned to make films about England or Englishness or whatever you call it. I think the subject matter of my films, without wanting to sound in any way pretentious, is universal. Because actually my films are about living and dying and work and relationships, family and children, having children and not having children, sex, all the things that are universal. The milieu, the tapestry, is where we are, which is in England. But when I’m making something I don’t think, “ah, now I’m capturing the zeitgeist…!”

DD: As a viewer I tend to resist the “Spielbergian” lures that are put into a film to make the viewer cry. You don’t aim for that at all, but I have found myself incredibly moved by the subtly emotional moments in your films.

DD: As a viewer I tend to resist the “Spielbergian” lures that are put into a film to make the viewer cry. You don’t aim for that at all, but I have found myself incredibly moved by the subtly emotional moments in your films.

ML: Because it’s real. That’s a lot in life. No disrespect to Steven Spielberg, for whom I have a lot of respect, and I gather it’s mutual. But I’m not in the business of pointing you, pushing you and pulling you in the directions of your emotions. My films operate on the principle that they’re about real people, and real people are the audience. I do not make films which arrive at a conclusion and tell you what simple, single emotion or thought or idea to go away with. I leave you with complex, contradictory stuff for you to ponder and argue and reflect on. That’s what is happening emotionally on the journey within the film as well.

DD: Humor is your secret weapon. Even in a very dark film like Naked, the dialogue and the attitudes of the characters in many scenes provokes immediate laughter. Are you thinking of the audience reaction when you’re directing?

ML: People ask me, “when do you decide where it should be funny and where it shouldn’t be funny?” I don’t. It looks after itself, because life itself is comic and tragic. That’s how it comes out of the scene; you mine it out of the soil.

I don’t know how you would make a film if you weren’t constantly in a state of preoccupation with the audience, because that’s what my job as a filmmaker and a storyteller is. I am the representative of the audience. I’m there to say, “Do they get this, would it be better if it was like this, should we reverse the order of those shots?”

But that’s not the same thing as deciding whether it’s going to be funny. The principle of how I think my work operates for the audience is that we’re starting from the premise that it’s real. You’re watching something that’s really going on. And then you will decide what you feel about it. The one thing I don’t do is make films that leave you with anything other than a highly ambivalent and complicated set of things to think about.

|

Buy or Rent Mr. Turner

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

Leave a Reply